Companies invested more than $16 billion dollars to sponsor North American sports during 2017. In an era of Netflix, cord-cutting, and DVR, brands increasingly rely on sponsorship to connect and engage with consumers around a point of passion. But do fans care about sponsors? Does sponsorship enhance a brand's reach and favorability? The answer, of course, is it depends. A fan in the team's home market rejects or embraces sponsors in a different manner than a fan isolated from the team. But not in the way you might expect.

Logically, one might surmise that sponsorship is most effective with in-market fans. And it is, to some degree. But, according to new research from assistant marketing professors Conor Henderson and Joshua Beck at the University of Oregon's Lundquist College of Business and Marc Mazodier, associate professor at Zayed University College of Business, there is untapped potential in out-of-market “isolated" fans.

Through a series of studies detailed in their paper “The Long Reach of Sponsorship: How Fan Isolation and Identification Jointly Shape Sponsorship Performance," Henderson, Beck, and Mazodier uncovered an interesting phenomenon: strong fans of sports teams who were isolated from their favorite team were significantly more likely to recall a team's brand sponsor than strong fans in-market. In addition, weak fans that were isolated (for example, because they moved to a new location) were more likely to avoid brands that sponsored the team.

“Across our studies we witnessed a ‘doubling-down" for isolated strong fans that included enhanced memory, attitudes, word of mouth, and purchase intentions. But the opposite was true for isolated weak fans, who actively avoided brands that support the team," said Henderson.

In the researchers" first study, participants were asked to simply recall the primary brand sponsor of their team, which prominently appears on athletes" jerseys. The study was conducted with 389 fans of a Premier League team in the United Kingdom and repeated for 291 NBA fans of the Los Angeles Lakers, which had recently introduced a sponsor brand (e-commerce retailer Wish) on the team's uniforms. Among the Premier League fans, brand recall was 28 percent higher for strong fans in more isolated contexts compared to strong fans in less isolated contexts. Similarly, among the strongest Lakers fans, purchase intentions were 39 percent higher among the strongest Lakers fans in isolated contexts.

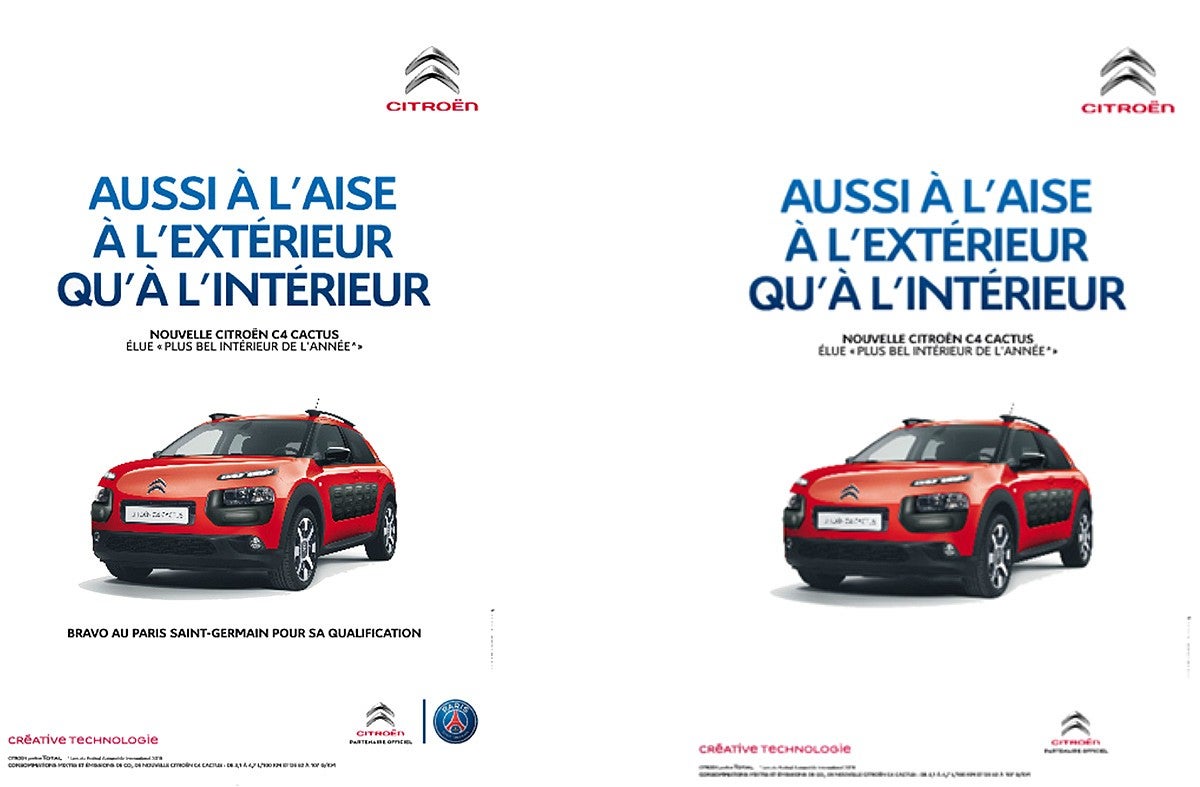

In a second study, 288 fans of Paris Saint Germain (PSG), a professional soccer team in France, were asked to read a 16-page newspaper that included six advertisements. One of the advertisements was from the French automobile brand Citroën. For some participants, the Citroën ad referred to its sponsorship of PSG, along with the PSG logo. Other participants saw an altered version of the Citroën ad with the sponsorship information and PSG logo removed. After reading the newspaper and providing open-ended feedback about the layout, participants listed all of the brands they could recall from the advertisements. When the team logo was present 55 percent of strong fans recalled Citroën if they were less isolated, but recall jumped to more than 83 percent in the more isolated condition. For weak fans, again, the pattern flipped to reveal a desertion effect. Only 17 percent of weak fans recalled Citroën from the ad with sponsorship in the more isolated condition, compared with 52 percent among weak fans in the less isolated condition.

“We found the reversal with weak fans particularly interesting," Henderson noted. “There is a desertion effect that implies that weak, isolated fans actively avoid vestiges of their fan identity that interfere with their efforts to affiliate with their more proximal social environment."

The third study used web ads that associated brands with NFL teams. Participants in this study were asked to first complete a writing task as a means of gauging their feeling of isolation as fans of particular NFL teams. After the writing test, they were asked to read an article about the team's upcoming season schedule that contained an ad for Chevrolet with the logo of their team. Participants were then asked questions to measure their sponsor brand attitude, as well as demographic questions. Once again, analysis revealed that fan isolation had a positive and significant effect on sponsor attitude among strong fans and that isolation lead to less favorable attitudes toward the sponsor for weak fans. The researchers repeated the study using Chipotle in place for Chevrolet with the same results.

Taken altogether, the three sets of studies employed different methods involving 1,412 real-life sports fans across multiple sports and countries. In each case, fan isolation and identification were shown to jointly determine how receptive fans are to sponsorship. The implications are that understanding and accounting for fan isolation opens up new avenues for sponsors to engage with and activate a team's strongest fans.

As the authors note, “This research offers new insights for branding and advertising efforts that seek to build connections to consumers around points of passion."

This can be particularly true in the context of social media and online advertising, in which managers are able to target isolated strong fans. The research also points to the importance of brands being precise in their targeting online so as to not drive away weak fans. Lastly, as the authors point out, although the feeling of isolation is rooted in one's psychology, it corresponds to how physically distant fans are from the team, which is information marketing managers can gather and use.

“Local brands that sponsor local teams should keep in mind that weak fans are equally receptive as strong fans," Henderson also noted. “Local sponsors should not narrowly target strong fans or use overly nuanced promotional messaging that weak fans might fail to comprehend."

The paper has been conditionally accepted for publication at the Journal of Marketing and is currently published as an MSI working paper.